Silas Burke’s Position as a Slaveowner in Fairfax County

It is important to challenge the interpretation by the Fenton Project of Silas Burke’s position within the overall slaveowner population of Fairfax County. At public meetings and on the Fenton Project webpage, Donald M. Sweig’s study: ‘Northern Virginia slavery: a statistical and demographic investigation’ has been partially displayed with sidenotes stating that Silas had 13 enslaved people in 1850 and ‘56% of households owned no slaves at all.’ In verbal interviews with the Fenton Project it has been inferred that Silas was a ‘prolific enslaver.’

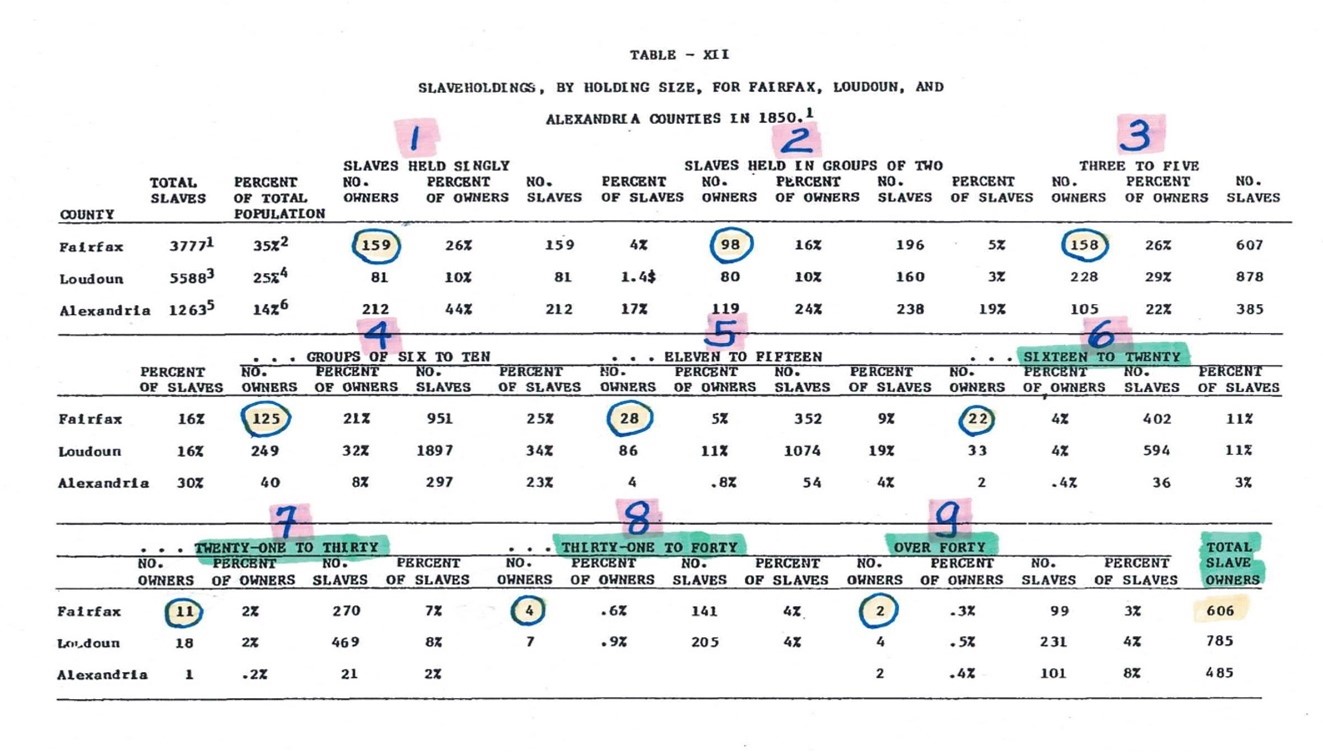

Below is the full Sweig Chart with Fairfax County highlighted. Sweig set up 9 categories to define how many slaves were held, showing the percentage of slave owners in each of the 9 categories. Silas Burke had 13 slaves as listed on the 1850 Slave Schedule filed with Fairfax County. 13 is Category 5 (11-15 slaves). Categories 6-9 have more than 15 slaves. Categories 1-4 have less than 11 slaves. Silas is in the middle category.

In category 5, there were 28 owners who had 11-15 enslaved people. Generally, these owners had more than 100 acres of land. Silas had approximately 187 agricultural acres – inherited from his father, James Burke. Silas also inherited the enslaved people from his father’s Estate.

The higher the category (6-9) the more land the owner had. Generally by 1850, many of the larger land owners were several generations removed from the original family landowner. Land was passed and divided through family inheritance, including associated enslaved people.

Northern Virginia slavery: a statistical and demographic investigation, William & Mary, Ph.D. thesis, Donald M.Sweig

94% of slaveowners in Fairfax County had less than 15 slaves (Categories 1-5).

Fenton Project uses 10%/90% figure which is mathematically inaccurate – but basically the bottom line remains the same. Silas was in the Group that has less than 15 slaves, which was the majority of Fairfax County slaveowners.

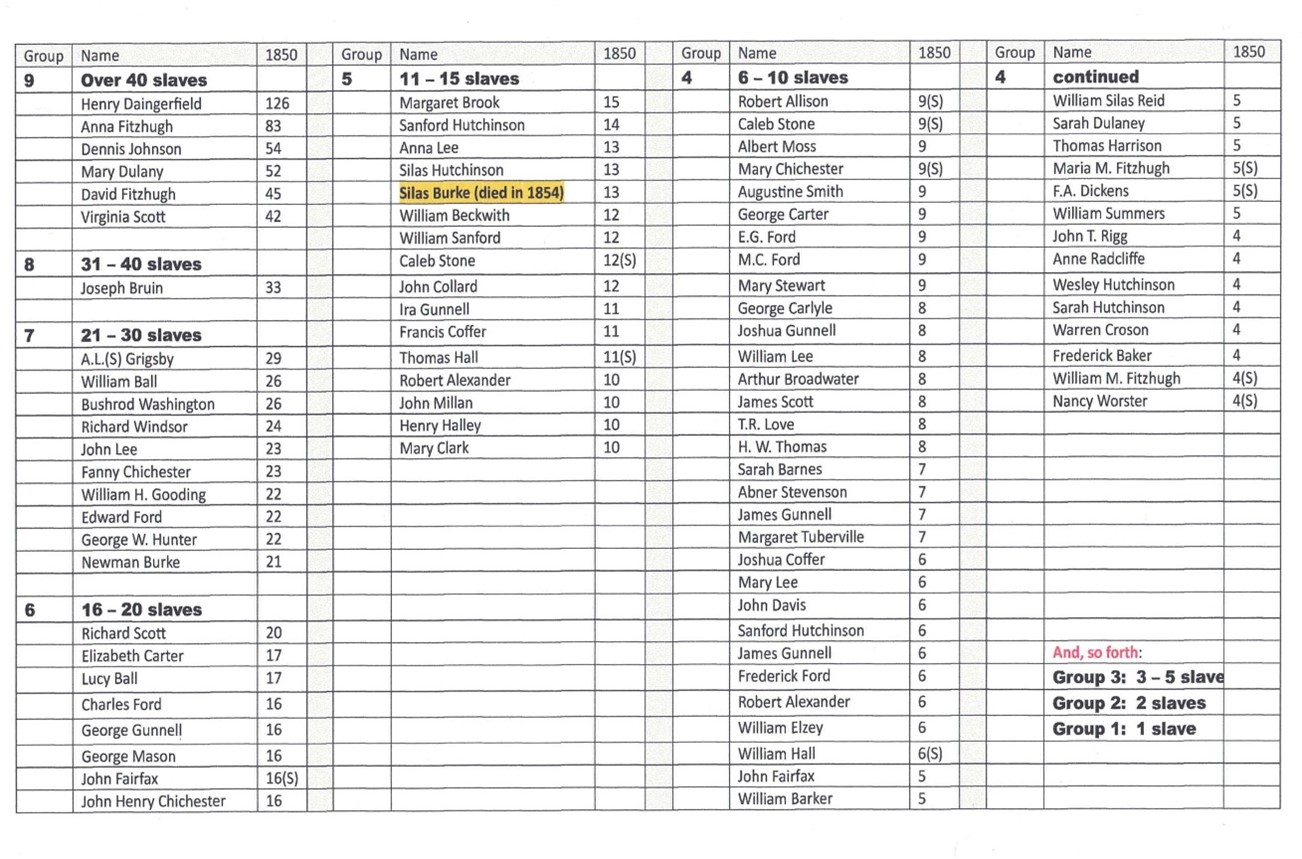

The chart below shows numbers taken from the 1850 Slave Schedules filed with the Fairfax County Court. It puts into perspective Silas’ position and addresses the comment by Fenton Project that he is a ‘prolific enslaver.’ Silas had 13 slaves on his personal farm. One of his employers, William Henry Fitzhugh, who owned 22,000 acres, had many more. As part of Silas’ job he oversaw the general administrative running of ‘Ravensworth.’ Fitzhugh, during his ownership, did not increase his slaves, rather, he downsized the number of slaves he inherited from his father. Silas, in his administrative position at ‘Ravensworth,’ would have been a part of that downsize in addition to administration of Fitzhugh’s will provisions to free all ‘Ravensworth’ slaves by schedule in 1850. Silas was also a busy Fairfax County attorney/agent and as such, performed his job in accordance with the laws of that time which he was required under oath to do. In the death of a client, handling estate distributions according to their will was his sworn duty. Silas’ placement is reflected below:

KEY:

| Group 9: Over 40 slaves |

Group 6: 16 – 20 slaves |

Group 3: 3 – 5 slaves |

| Group 8: 31 – 40 slaves |

Group 5: 11 – 15 slaves |

Group 2: 2 slaves |

| Group 7: 21 – 30 slaves |

Group 4: 6 – 10 slaves |

Group 1: 1 slave |

Looking at the ages of the slaves adds perspective. Silas’ 13 slaves were:

- 2 males at 34/30 yrs. old

- 2 females at 34/35 yrs. old

- 9 children: 3 under 5 yrs. old; 2 at 7 yrs. old and 4 under 14 yrs. old

Slaves had children. The ages and division of adult male-to-female is indicative of family units. Silas’ everyday work on the Ravensworth farm included the maintenance of slave families as units where parents, children, and extended family members were grouped together. This is documented in various articles with the sources cited below.

The Fenton Project continually infers that Silas appears to be unusually interested in children. This is a disparaging effort to suggest to readers a supposition that has no basis – whether that is on Silas’ personal farm or in his work performed at Ravensworth or for client estates that he represented as an attorney/agent.

Will of Silas Burke dated 1846, 8 yrs. before he died

Silas does not mention or gift any slave to anyone in his will. At that time in history, it was common for a slaveowner to bondage certain named slaves, especially household slaves, to members of their immediate family extending the bondage of that slave to the recipient person. By not doing so in his will, more options were available for the future of his enslaved people. The 1850 Slave Scheduled listed 13 slaves. When Silas died 4 years later in 1854 he had 14 slaves, an increase of 1. This is evidenced by the Inventory prepared by John A. Marshall (his overseer), witnessed by 2 persons, and filed with the Court in his estate action. It appears that 1 person may have been a child or an elderly person as the assigned value set is considerably lower than the others. This type of value was common for an elderly person or a very young child -which would logically be the child of one of the 13 enslaved people.

It is worth noting that neither Fenton nor Silvia are listed on the inventory of Silas Burke’s Estate (See Fenton and Silvia section in the sidebar). Either ‘both’ Fenton and Silvia died between 1826 (arrival on Silas’ farm) and 1854 (death of Silas – a 28 yr. span) or perhaps freedom to the North could have been arranged. It is also worth noting that there are several persons named Fenton Burke in New York in a timeframe that fits Fenton’s birth who have no genealogical connection that connects to an origin). It is also noted that there are no ‘Sale/Auctions’ advertised in The Alexandria Gazette of any slaves from Silas’ personal property during this 28-year span, and they are not listed among the Ravensworth slaves which Silas represented and who were set free in 1850.

Addressing ‘56% of households owned no slaves at all’ - from Fenton Project slide presentation

It is important to name a few factors that effected this percentage as the reference appears to bring forward a negative reflection towards Silas Burke’s ownership of 13 enslaved people in 1850:

- The slave population of Fairfax County had declined in the three decades between 1820 and 1850 with the number of Fairfax County slaves decreasing by over 30% by 1850, thus an increase in households without slaves. This resulted from a changing and declining economy in Fairfax County by 1850 due to an agricultural depression in the County. Many local planters now had more slaves than they needed for their own land. This circumstance shifted ownership numbers downward through various techniques which is widely documented in articles and books.

- At this same time, large landowners, together with their slaves, were migrating out of Fairfax County – going ‘west’ to more fertile agricultural land because of the depleted soils of Fairfax County – whether that was out to Loudoun County or much further west, including leaving the State of Virginia. This movement reduced the percentage of slaves and increased the number of households without slaves.

- Northern Quakers migrated to Fairfax County and purchased over 2,000 acres near Mount Vernon (Woodlawn) introducing forestry as their industry, cutting local white oak forests to sell to northern shipbuilders. This demonstrated to local farms that they could operate profitably, with free white man labor, rather than black slave labor. The population of Quakers in the area in 1850 was approximately 69, according to The Friends Society of Woodlawn Historian, none of whom owned slaves. This is a factor that makes up a part of that 56% number.

- As a result of the agricultural depression in Fairfax County, and the growth of the seat of government in Washington, DC., those dynamics changed the re-population of the area. People coming in from the North who were attracted to Fairfax County for its now depressed land prices rejected slave labor and believed in salutary effects of free labor. This, too, increased the percentage number of households without slaves.

- Landowners found it more profitable to sell their enslaved workers out of Fairfax County to more agriculturally based areas (Loudoun County and more southern States) than continue to cloth, feed, and house them. Thus, this type of non-ownership activity effected that 56% number.

- Manumission Wills, Freedom Purchases, and gradual/compensated emancipation was becoming more common in Fairfax County at this time. Such examples are Robert Carter and William Fitzhugh who by releasing their slaves changed the percentage of households without slaves in Fairfax County.

Above sources:

This was a period of change in Fairfax County as to enslavement. Silas died in 1854. His ownership was in the middle Group 5, at 13 enslaved people, not among the much higher slave owners recorded on the 1850 individual Slave Schedules. He still held the same land at his death that he inherited. He had already contemplated how to handle freeing his slaves as outlined in the National Tribute Article referenced on the ‘Save Burke’ Page. It is a supposition to place a narrative on the plans of Silas Burke. Attempts to misuse these percentages to disparage the character of Silas Burke and fabricate a reason to change a town’s name is unwarranted.